What is Takayasu Arteritis?

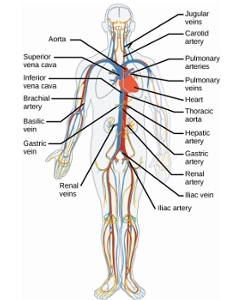

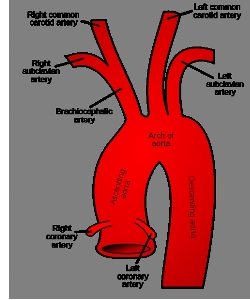

Takayasu Arteritis (TA) is a form of Large Vessel Vasculitis (LVV) with onset typically under the age of 50 years. Inflammation occurs in the large ateriers, particularly the aorta (the main artery taking blood from the heart to the rest of the body) and its main branches such as the sunbclavian arteries which supply blood to the arms. It can affect the renal arteries to the kidneys, the coronary arteries in the heart and the carotid arteries which take blood to the brain (see illustrations below).

In most cases (90%) the inflammation leads to narrowing of the vessels making it harder for blood to travel through them, hence TA is also known as “Pulseless disease” and often the absence of a pulse at the wrist leads to diagnosis of the disease. In around 25% of patients part of an artery may also get bigger, forming an aneurysm.

Illustrations above: Circulation diagram sourced from the “Arteries, Veins, and Capillaries” section of Robert Bear and David Rintoul’s article, “The Circulatory System,” Connexions, August 19, 2013, The Circulatory System. Aorta – Ascending, Arch & Descending diagram sourced from: “Gray’s Anatomy” Wikipedia Commons, Aorta diagram.

What causes Takauasu arteritis?

The cause of Takayasu’s arteritis, and why an individual develops the disease at any one time remains unknown. The disease is most likely to be the consequence of environmental factors and a susceptible genetic background. One common but unproven hypothesis is that it is precipitated by an infection. The rarity of the disease worldwide means that it is very difficult to identify an underlying cause. The inflammation involves white blood cells invading the wall of the artery predisposing to damage and scarring.

Who are affected?

TA is a rare disease with the initial symptoms arising in those between 5 and 40 years of age. Although both sexes may be affected, 80-90 per cent of patients are female. TA has worldwide prevalence and may affect all races. However, the disease is thought to be more common in patients originating from the Far East, Japan and the Asian sub-continent. As far as we know, TA is not a genetically inherited disease. It is unusual for more than one family member to suffer from the disease. However, the increased prevalence in certain parts of the world may indicate a genetic component to disease susceptibility and current studies are investigating this.

What are the symptoms?

The initial symptoms of TA are typically non-specific and may include one or more of:- malaise (a general feeling of being unwell), profound fatigue, fever, night sweats, weight loss, myalgia (muscle pain), arthralgia (painful joints), rash. Additional symptoms can include dizziness/light headedness, shortness of breath, cramping pain in the arms, legs or chest on exertion. Carotidynia, (pain and tenderness over the carotid arteries in the front of the neck) is also found in approximately 25 per cent of patients.

Making a diagnosis

This is made on the basis of formal criteria such as those published by the American College of Rheumatology. For diagnosis the patient should fulfil three or more of the criteria listed below:

Diagnostic Criteria for Takayasu’s Arteritis

- Onset of disease = 40 years

- Claudication** of an extremity

- Reduced brachial artery pulsation

- Difference in systolic blood pressure >10 mmHg between the arms

- Aortic or subclavian artery bruit

- Angiographic abnormality

** Claudication – severe muscle pain due to cramp, caused by narrowed blood vessels, on use of the extremity – a good example of this is hanging up washing where the arm affected become painful

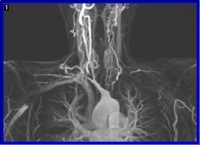

In practice clinical examination most commonly detects decreased or absent pulses in the arms and less frequently in the legs. Using a stethoscope, bruits*, (a loud ‘whooshing noise’) may be detected, over the neck, chest or kidneys indicating narrowed arteries. High blood pressure is commonly found. In recent years specialist scans have been introduced to aid diagnosis and identify inflammation, narrowing and dilatation of arteries and the extent of the disease. These include positron emission tomography (PET scanning), magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), high-resolution ultrasound and CT angiography (see below). There is not one single test that alone can diagnose and map out the extent of vessel involvement and typically patients will have a series of scans at diagnosis and then more at regular intervals for follow up.

Diagnostic tests

Blood Tests: There is no blood test that can be used to definitively confirm the diagnosis. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) can help measure inflammation as a marker of activity of the illness and your response to treatment.

Imaging: Imaging studies are useful in the diagnosis and monitoring of TA. Their use may allow diagnosis before arterial damage is severe. However, none of them are 100 per cent accurate. We now use “multimodaility” imaging, a combination of ultrasound, CT and MRI.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is commonly used to aid diagnosis and assess the extent of TA. The scan does not involve radiation and the picture of the arteries can be enhanced by using a contrast medium (that only rarely causes an allergic reaction).

MRI is a safe means by which to monitor the progress of disease and response to treatment. The main drawbacks are that the scanner is very noisy and rather claustrophobic. The illustration shows an MRI scan of a TA patient.

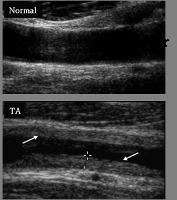

Ultrasound – Doppler ultrasound (ultrasound scan): uses a probe which is passed over the carotid arteries in the neck. This allows assessment of blood flow and can detect and monitor the arterial wall and the degree of narrowing.

This illustration shows a normal carotid artery and one from a TA patient. The arrows show the thickening of the artery wall causing the narrowing of the artery.

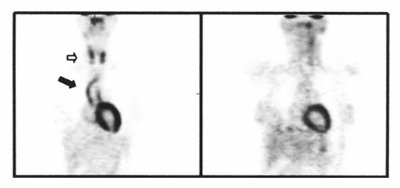

Positron emission tomography (PET scanning): requires the patient to be injected with radioactive fluorodeoxyglucose. PET scans are particularly good at detecting inflammation in the arterial wall and are often used in combination with CT scanning (CT-PET). PET may identify early active disease and may on occasion help to distinguish active disease (which needs further treatment) from scarring resulting from previous inflammation. The illustration shows two PET images from the same patient; the one on the left is before treatment, with the arrows pointing to areas of inflammation. These areas have disappeared in the image on the right which was taken after six months treatment.

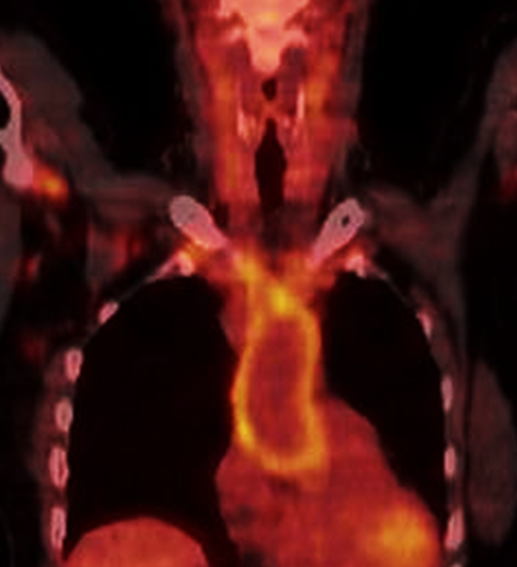

Image above shows a combined PET-CT scan showing increased uptake (yellow) in an enlarged aorta (the blood vessel arising from the heart)

Computed tomography (CT) angiography: Contrast-enhanced CT angiography is useful for the diagnosis of TA and can help identify the extent of damage to the arteries. Unlike MRI/MRA and Doppler US, CT angiography does involve radiation.

Treatment

Treatment is aimed at preventing further damage and/or scarring to the blood vessels and improving symptoms. When there is active inflammation in the arteries, treatment is started with steroids, usually prednisolone, and often in combination with immunosuppressant drugs. Those commonly used include methotrexate, azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil. These drugs increase the effectiveness of steroid therapy and help to reduce the dose of steroids required. Steroids have many side effects and current practice is to minimise their use oer time but using other immunosuppressive medications. In recent years, for refractory disease (that remains active despite steroids and tablet immunosuppressive medications), biologic therapies, interleukin-6 inbitior’s (tocilizumab and sarilumab) is used. Tumour necrosis factor inhibitors such as etanercept, adalimumab and infliximab have also been used successfully. In patients with persistent or very severe disease, especially that involving the heart or brain, the stronger medication cyclophosphamide may be recommended.

Additional treatment: It is curcial to ensure no further narrowing of blood vessels occurs. Therefore risk factors such as high cholesterol and high blood pressure need to be controlled. Drugs to lower blood pressure are often recommended. Statins are commonly prescribed to lower cholesterol and reduce the risk of heart disease. In TA statins and certain blood pressure drugs may also have a beneficial effect on arterial function, even when cholesterol levels are normal. Low-dose aspirin may be prescribed in some cases to reduce the risk of a blood clot developing. If high doses of steroids are required drugs to prevent osteoporosis (weakening of the bones) may also be prescribed.

Surgery: Surgical intervention should not be undertaken lightly and is only indicated for the most severe cases of TA. For optimal results surgery should be carried out when the disease is in remission and decisions will involve a team of specialist doctors including the rheumatologist, vascular surgeons and radiologists. Procedures that may be carried out include:

Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) – aims to open narrowed arteries by inserting and inflating a balloon to stretch the narrowed section. In some cases a wire mesh (stent) may be required to keep the artery open. This is successfully used to unblock the arteries to the kidneys (renal arteries) to reduce blood pressure.

Drugs and Side effects

For information on the main drugs prescribed for Takayasu Arteritis see:

Pregnancy and Takayasu arteritis

Many women with Takayasu’s arteritis achieve one or more successful pregnancies.

It is very important for a woman planning to have a baby to talk to her specialist before trying to conceive. Depending on how advanced your disease is and how much damage has been done to your arteries, it may on occasion be dangerous for a woman to carry a baby. For example control of blood pressure can be difficult in patients with TA and blood pressure can be increased by pregnancy to a dangerous level. Likewise, high pressure in the pulmonary (lung) circulation can place a woman at significant risk during pregnancy.

Unless the disease is very active, TA itself will not affect your fertility, whether you are a man or a woman. However, some of the drugs used to treat the condition may reduce fertility, Likewise, other medications may increase the risk of defects in the foetus. It is therefore essential for both women and men with TA to consult their specialist to discuss all aspects of starting a family.

Prognosis

The long term prognosis of TA is good. Approximately 20 per cent of patients will have a monophasic self-limiting disease (just one inflammatory episode). More typically, the disease follows a relapsing and remitting course. Limited data are available on long-term outcome and varies significantly between patients, dependent upon the extent of their disease. In the majority of patients the TA appears to ‘burn out’ after a period of 2-5 years, and treatment can be gradually withdrawn. The figures below summarise data from surveys performed around the world:

- 25 per cent of patients largely unaffected by their disease

- 25 per cent of patients able to perform normal daily activities when disease in remission

- 50 per cent were unable to consistently do or maintain their full range of daily activities

- Up to 25 per cent of patients are unable to work due to their Takayasu’s arteritis

With early intervention and careful monitoring in a specialist centre TA can be effectively treated. Mortality rates are low with survival in the USA and UK up to 98 per cent at 10 years. Mortality directly related to TA is usually the consequence of heart attack, heart failure, aneurysm rupture, stroke or kidney failure. These events are reduced with regular monitoring and careful attention to blood pressure treatment.

Key Points

- TA is very rare in the UK and mainly affects young women

- Presenting symptoms are often non-specific and missed – a diagnostic delay is common

- Treatment with steroids and immunosuppressants is effective in most cases

- Surgical repair or angioplasty to narrowed blood vessels should only be performed in severe cases and after the inflammation is controlled

This page has been updated by Dr Taryn Youngstein, Co-Director of the Imperial College London Centre for Vasculitis Research. Vasculitis UK is indebted to the late Professor Justin Mason of Imperial College, London, for authoring the original version of this web page on Takayasu Arteritis.

The authors of this page have recently published a detailed and up-to-date review (Primer) on Large Vessel Vasculitis for the publication Nature. This is available here.

Related Vasculitis Articles

- Fertility and Vasculitis – Dr David Jayne

- Vasculitis in Children – Dr Paul Brogan

Further reading

- Large Vessel Diseases – Ashima Gulati, Arvind Bagga

- Vasculitis Paediatric Guidelines 2012 – Dr Helen Foster & Dr Paul Brogan, Oxford University Press

This page was last updated in February 2024