Anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibodies (ANCA)

Mark E. McClure, Vasculitis Research Fellow, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge

Rachel B. Jones, Consultant in Nephrology and Vasculitis, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge

ANCA-associated vasculitis

If a patient has ANCA-associated vasculitis, he or she may have one of three different vasculitis conditions: 1. granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), previously known as Wegener’s granulomatosis, 2. Microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) and 3. eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), previously known as Churg-Strauss syndrome (1). These three conditions are grouped together under the umbrella term ‘ANCA-associated vasculitis’ because they are all associated with a key protein factor in the blood called ‘ANCA’ and because they all cause inflammation or damage to small blood vessels. Small blood vessels are found all over the human body, so any part of the body can be affected, but most commonly the kidneys, lungs, joints, ears, nose, and nerves. Because the kidneys and lungs are vital organs, early treatment for ANCA-associated vasculitis is very important to prevent serious organ damage.

Antibodies and autoantibodies

The human body is well designed to fight infections and prevent the development of cancers using the white blood cells and protein factors that comprise a healthy immune system. A key element of our immune system is its ability to distinguish between the human body’s own cells (referred to as ‘self’) and foreign cells e.g. bacteria and viruses (‘non-self’). Each cell carries protein markers called antigens that allow it to be identified as ‘self’ or ‘non-self’ by the immune system. Antibodies (also known as immunoglobulins) are important blood proteins in the immune system that are produced by a type of white blood cell called B cells. Antibodies naturally develop during exposure to infection and by binding to foreign antigens, help neutralise and eliminate the particular ‘non-self’ bacteria or virus that caused the infection. Antibodies are especially helpful when a particular type of bacteria or virus is encountered for a second time. In this situation antibodies already present in the blood against the particular bacteria or virus, prevent infection from developing. Stimulating the formation of antibodies against potentially serious infections by exposure to a mild or killed version of a bacteria or virus is the principle of vaccination. Antibodies against foreign ‘non-self’ cells are therefore very useful.

Autoimmunity is a failure of the immune system to always correctly recognise ‘self’. As a result, the body’s own immune system attacks part of the human body. Autoimmune conditions are often characterised by the production of antibodies against one type of human cell (so called auto-antibodies). Autoantibodies may directly cause harm, by binding to their specific cell type, causing the cell to malfunction.

What are ANCA?

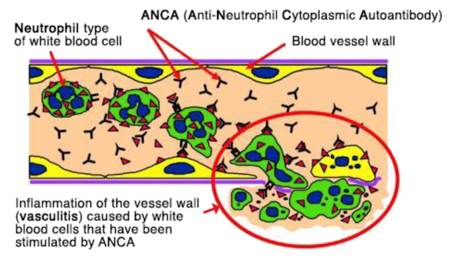

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibodies (ANCA) are autoantibodies that target a type of human white blood cell called neutrophils, which are important in health for fighting infection partly through the release of toxic substances that destroy bacteria. In ANCA-associated vasculitis, ANCA specifically bind to two proteins that are normally found in the fluid within the neutrophil (cytoplasm). The two proteins are called proteinase 3 (PR3) and myeloperoxidase (MPO). Patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis usually have autoantibodies against PR3 (PR3-ANCA) or MPO (MPO-ANCA) but not both. In granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA, Wegener’s) 95% of patients are ANCA positive at diagnosis, and GPA is most commonly associated with PR3-ANCA (~65% patients). In microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) 90% of patients are ANCA positive at diagnosis, typically with MPO-ANCA (~55% patients) (2). However, in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA, Churg Strauss) only 40 % of patients are ANCA positive at diagnosis, usually MPO-ANCA(3).

ANCA contribute to blood vessel damage

ANCA are not only a measureable blood marker in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis but they are harmful autoantibodies that are directly involved in small blood vessel damage. The binding of ANCA to neutrophils in the blood, results in: 1 the release of toxic substances from neutrophils causing damage to small blood vessel walls, 2 neutrophil migration through blood vessel walls causing inflammation in surrounding tissues, 3 release of signalling factors that attract more neutrophils, perpetuating the inflammation and destruction of small blood vessels (4). ANCA alone are capable of causing vasculitis, as observed in a baby who developed lung and kidney vasculitis after birth, because MPO-ANCA had crossed the placenta from the mother(14). Furthermore, medications including propylthiouracil, hydralazine and penicillamine have been associated with the development of ANCA and vasculitis. Stopping the medication usually results in clinical improvement and the disappearance of ANCA from blood (13).

Where do ANCA come from?

There is evidence that both genetic susceptibility and environmental exposures contribute to the aetiology of AAV(5). However, the actual mechanism by which ANCA arise in different people at different ages is poorly understood. Infections are one possible trigger; 63% of patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA, Wegener’s) chronically carry the common bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus in their noses, and nasal inflammation is common in GPA (6). Another proposed mechanism is ‘molecular mimicry’ between bacterial and self-antigens, when similarities between foreign and self-antigens may be sufficient to activate immune cells (7). Alternatively ANCA may result form defective neutrophil cell death, resulting in abnormal exposure of internal neutrophil fragments (8).

ANCA testing

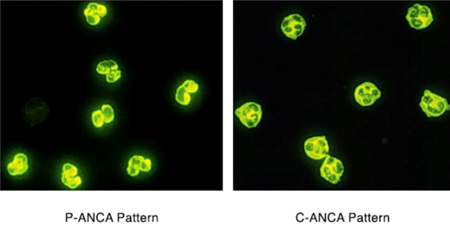

ANCA blood tests are performed by two methods: Indirect Immunofluorescence (IIF) and Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbant Assay (ELISA). Indirect immunofluorescence identifies ANCA by staining patterns withn neutrophils. ANCA staining throughout the neutrophil cytoplasm (C-ANCA pattern) usually occurs with a PR3-ANCA. Staining around the cell nucleus (perinuclear pattern) usually occurs with MPO-ANCA. Immunofluorescence testing provides a positive or negative result. Conversely ELISA is a technique that allows the level of PR3 or MPO-ANCA to be measured. Historically, immunofluorescence has been used to screen patients for ANCA, followed by ELISA to measure the amount of PR3-ANCA or MPO-ANCA present(17).

How useful are ANCA blood tests?

Testing for ANCA at the time of diagnosis of ANCA-associated vasculitis is really useful. A positive C-ANCA immunofluorescence test or a strongly positive PR3-ANCA or MPO-ANCA ELISA test result is highly suspicious for the diagnosis of ANCA-associated vasculitis. Provided that a patient has clinical features of vasculitis, the positive ANCA test helps to confirm the diagnosis along with tissue biopsy results. The introduction of ANCA testing across the UK in the 1980s was associated with a significant increase in the diagnosis of ANCA-associated vasculitis, probably because ANCA tests allowed more cases of ANCA-associated vasculitis to be correctly identified.

After a diagnosis of ANCA-associated vasculitis has been made, regular blood testing for ANCA is part of routine clinical care. Importantly patients with PR3-ANCA at diagnosis have a higher long term relapse risk (50% relapse at 5 years) compared to those with MPO-ANCA at diagnosis (20-30% relapse risk at 5 years). Typically both PR3-ANCA and MPO-ANCA levels fall during treatment, and most but not all patients become ANCA negative over many months. ANCA testing can be very helpful for some individual patients for predicting the timing of a relapse, with a switch from ANCA negative to ANCA positive or a rise in ANCA level predicting relapse. However, these rules do not consistently apply to all patients, making the interpretation of ANCA results less straightforward. For example a minority of patients suffer relapses when they are ANCA negative, and others relapse without a significant rise in their ANCA level. ANCA tests results are therefore always interpreted along side clinical assessment and other blood test results such as inflammatory markers (CRP, ESR), kidney function and urine measurements for blood and protein.

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, Basu N, Cid MC, Ferrario F, et al. 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum [Internet]. 2013 Jan [cited 2016 Nov 24];65(1):1–11. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/art.37715

- Christiaan Hagen E, Daha MR, Hermans J, Andrassy K, Csernok E, Gaskin G, et al. Diagnostic value of standardized assays for anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in idiopathic systemic vasculitis for the EC/BCR project for ANCA assay standardisation. Kidney Int. 1998;53:743–53.

- Sablé-Fourtassou R;, Cohen P;, Mahr A;, Pagnoux C. Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibodies and the Churg-Strauss Syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(9).

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ. Pathogenesis of antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-mediated disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol [Internet]. 2014 Jul 8 [cited 2016 Nov 26];10(8):463–73. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrrheum.2014.103

- Lyons PA, Rayner TF, Trivedi S, Holle JU, Watts RA, Jayne DRW, et al. Genetically distinct subsets within ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2012 Jul 19 [cited 2016 Nov 26];367(3):214–23. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22808956

- Stegeman CA, Tervaert JW, Sluiter WJ, Manson WL, de Jong PE, Kallenberg CG. Association of chronic nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus and higher relapse rates in Wegener granulomatosis. Ann Intern Med [Internet]. 1994 Jan 1 [cited 2017 Mar 19];120(1):12–7. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8250451

- Kain R, Exner M, Brandes R, Ziebermayr R, Cunningham D, Alderson CA, et al. Molecular mimicry in pauci-immune focal necrotizing glomerulonephritis. Nat Med [Internet]. 2008 Oct [cited 2016 Nov 27];14(10):1088–96. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18836458

- Ohlsson SM, Pettersson Å, Ohlsson S, Selga D, Bengtsson AA, Segelmark M, et al. Phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages in anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated systemic vasculitis. Clin Exp Immunol [Internet]. 2012 Oct [cited 2017 Mar 19];170(1):47–56. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22943200

- Finkielman JD, Merkel PA, Schroeder D, Hoffman GS, Spiera R, St Clair EW, et al. Antiproteinase 3 antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and disease activity in Wegener granulomatosis. Ann Intern Med [Internet]. 2007 Nov 6 [cited 2017 Mar 19];147(9):611–9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17975183

- Jayne DR, Gaskin G, Pusey CD, Lockwood CM. ANCA and predicting relapse in systemic vasculitis. QJM [Internet]. 1995 Feb [cited 2017 Mar 19];88(2):127–33. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7704563

- Kyndt X, Reumaux D, Bridoux F, Tribout B, Bataille P, Hachulla E, et al. Serial measurements of antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies in patients with systemic vasculitis. Am J Med [Internet]. 1999 May [cited 2017 Mar 19];106(5):527–33. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10335724

- Russell KA, Fass DN, Specks U. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies reacting with the pro form of proteinase 3 and disease activity in patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis and microscopic polyangiitis. Arthritis Rheum [Internet]. 2001 Feb [cited 2017 Mar 19];44(2):463–8. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/1529-0131%28200102%2944%3A2%3C463%3A%3AAID-ANR65%3E3.0.CO%3B2-9

- GAO Y, ZHAO M-H. Review article: Drug-induced anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Nephrology [Internet]. 2009 Feb [cited 2017 Mar 19];14(1):33–41. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19335842

- Schlieben DJ, Korbet SM, Kimura RE, Schwartz MM, Lewis EJ. Pulmonary-renal syndrome in a newborn with placental transmission of ANCAs. Am J Kidney Dis [Internet]. 2005 Apr [cited 2017 Mar 19];45(4):758–61. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15806479

- Xiao H, Heeringa P, Hu P, Liu Z, Zhao M, Aratani Y, et al. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies specific for myeloperoxidase cause glomerulonephritis and vasculitis in mice. J Clin Invest [Internet]. 2002 Oct [cited 2016 Nov 27];110(7):955–63. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12370273

- Xiao H, Heeringa P, Liu Z, Huugen D, Hu P, Maeda N, et al. The Role of Neutrophils in the Induction of Glomerulonephritis by Anti-Myeloperoxidase Antibodies. Am J Pathol [Internet]. 2005 Jul [cited 2017 Mar 19];167(1):39–45. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15972950

- Houben E, Bax WA, van Dam B, Slieker WAT, Verhave G, Frerichs FCP, et al. Diagnosing ANCA-associated vasculitis in ANCA positive patients: A retrospective analysis on the role of clinical symptoms and the ANCA titre. Medicine (Baltimore) [Internet]. 2016 Oct [cited 2017 Feb 15];95(40):e5096. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27749588

- Boomsma MM, Stegeman CA, van der Leij MJ, Oost W, Hermans J, Kallenberg CG, et al. Prediction of relapses in Wegener’s granulomatosis by measurement of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody levels: a prospective study. Arthritis Rheum [Internet]. 2000 Sep [cited 2017 Mar 19];43(9):2025–33. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/1529-0131%28200009%2943%3A9%3C2025%3A%3AAID-ANR13%3E3.0.CO%3B2-O

- Han WK, Choi HK, Roth RM, McCluskey RT, Niles JL. Serial ANCA titers: useful tool for prevention of relapses in ANCA-associated vasculitis. Kidney Int [Internet]. 2003 Mar [cited 2017 Mar 19];63(3):1079–85. Available from: https://www.kidney-international.org/article/S0085-2538(15)48978-1/fulltext

- Kemna MJ, Damoiseaux J, Austen J, Winkens B, Peters J, van Paassen P, et al. ANCA as a predictor of relapse: useful in patients with renal involvement but not in patients with nonrenal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol [Internet]. 2015 Mar [cited 2017 Feb 15];26(3):537–42. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25324502

- Tomasson G, Grayson PC, Mahr AD, Lavalley M, Merkel PA. Value of ANCA measurements during remission to predict a relapse of ANCA-associated vasculitis–a meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) [Internet]. 2012 Jan 1 [cited 2017 Mar 19];51(1):100–9. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/rheumatology/article/51/1/100/1775555