Dr Harold Wilson-Morkeh (Doctoral Clinical Research Fellow & Specialty Registrar in Rheumatology & Internal Medicine)

Rheumatology Department, Hammersmith Hospital, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, London, UK

Professor Salman Siddiqui (Professor of Respiratory Medicine & NHS Consultant)

Respiratory Department, Hammersmith Hospital, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, London, UK

April 2025

What is EGPA?

Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (EGPA), formerly known as Churg-Strauss Syndrome, is the rarest form of ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) that results in inflammation in small and medium sized blood vessels. The lungs and sinuses are most commonly affected – almost all individuals with the disease have asthma, and polyps in the nose are a frequent occurrence – but it can also affect other organs including the heart, kidneys, nerves, skin and digestive tract.

What causes EGPA?

We don’t know exactly what causes EGPA, but it is thought to be an autoimmune disease (a type of disease where the immune system, the body’s natural defence mechanism, can’t tell the difference between your own cells and foreign cells and mistakenly attacks your own cells). As with other autoimmune diseases, genetic studies in EGPA have found genes that are linked to the disease, but this doesn’t appear to be the whole story. Key cells and antibodies produced by the immune system are also likely involved:

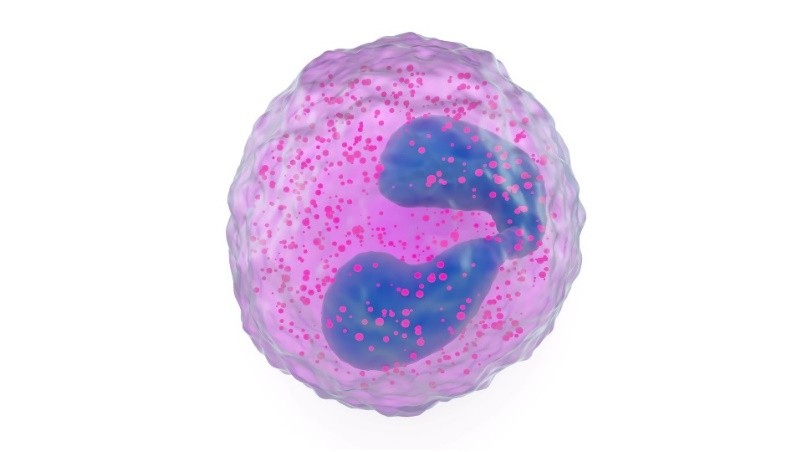

Eosinophils

Eosinophils are a type of white blood cell that typically fight parasite infections and are involved in allergies. They are found in high numbers in the blood and affected parts of the body in individuals with EGPA. Eosinophils can release harmful proteins which can damage tissues leading to inflammation.

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies or ANCA

EGPA is often grouped together with similar vasculitis conditions which are types of ANCA-associated vasculitis or AAV. Studies have found that approximately 30-40% of individuals with EGPA have ANCA. These antibodies have different staining patterns when looked at under a special light microscope after using a test called indirect immunofluorescence (IIF). ANCA can either stain around the nucleus or control centre of the cell (perinuclear, pANCA) or throughout the cytoplasm or liquid of the cell (cytoplasmic, cANCA). A second test called an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is then often performed to see if you have antibodies against 2 proteins: myeloperoxidase (anti-MPO) and proteinase 3 (anti-PR3). pANCA usually occurs with anti-MPO and cANCA with anti-PR3. pANCA and anti-MPO are more common in EGPA. ANCA are capable of directly triggering inflammation in blood vessels and damage in certain organs.

Who is affected?

EGPA seems to affect men and women equally. Around 10-14 people per million are diagnosed with EGPA around the world. The average age of diagnosis is 40 years old though it can occur very rarely in children and uncommonly in those over the age of 65.

What are the symptoms of EGPA?

Individuals with EGPA tend to develop symptoms affecting multiple organ systems over time. These can include the following:

- Almost all individuals will suffer from asthma, often occurring during adulthood. This can manifest with symptoms of cough, wheeze and shortness of breath.

- Chronic rhinosinusitis is frequent and refers to inflammation of the nasal tract and sinuses. This can lead to runny nose, sneezing, nasal congestion, sinus pressure and decreased smell and taste.

- Some individuals also develop nasal polyps (growths in the nose) that contribute to impaired smell and nasal congestion.

- Generalised joint and muscle aches and pains.

- Some individuals will also experience fever, night sweats, unintentional weight loss and fatigue.

As the disease progresses, symptoms can develop that reflect the migration of eosinophils into different organs and vasculitis in certain individuals:

- Lung: worsening wheeze and breathlessness, coughing up blood.

- Heart: chest pain, palpitations, difficulty breathing (particularly when lying flat or climbing stairs).

- Skin: rashes that can sometimes be itchy or painful.

- Digestive tract: difficulty and/or pain swallowing, acid reflux, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, blood in the stool.

- Nerves: inflammation and/or damage leading to tingling, numbness, weakness and/or pain of the hands, arms, legs and/or feet.

- Kidneys: inflammation can cause blood and/or protein to be present in the urine, but this doesn’t usually cause symptoms.

How is EGPA diagnosed?

EGPA can be difficult to diagnose because it is a rare disease. It can affect different organ systems at various times and can appear similar to different diseases, so it frequently requires a group of healthcare professionals from different specialties to work together in a multi-disciplinary team (MDT) to join all the dots. EGPA is more likely to be suspected if you have:

- A history of asthma and sinus symptoms

- Elevated eosinophil levels on a blood test

- Signs of eosinophilic inflammation or vasculitis on imaging tests and/or tissue biopsies

What diagnostic tests are performed in individuals suspected of EGPA?

Blood tests

- Full blood count (FBC) is a test that measures the number of different blood cells in your body. An FBC will show elevated levels of eosinophils in an individual newly diagnosed with active EGPA. The eosinophil count can be normal if the disease is inactive (i.e. after treatment). The FBC can also show anaemia (low haemoglobin) and high platelets indicating chronic inflammation.

- Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) are present in 30-40% of individuals with EGPA so testing for this can be helpful for diagnosis. It is important to remember that ANCA is not present in the majority of individuals with EGPA, however.

- Kidney function tests (urea and creatinine) can be elevated indicating kidney damage due to inflammation and scarring, though this is uncommon in EGPA.

Urine tests

- Urine tests are useful to see if inflammation or damage is occurring in the kidney. This will result in the presence of blood and/or protein in the urine. These tests can either be performed in the clinic (urine dipstick) or sent to the lab to be looked at under a microscope (urine microscopy) or analysed for a type of protein in your blood called albumin (urine albumin: creatinine ratio).

Chest X-ray

- People living with active EGPA may have patches on their lung which are visible on a chest x-ray. These patches often represent areas of the lung where eosinophils have migrated from the bloodstream and caused inflammation to the lung.

High-resolution CT scan of the chest

- This is a more detailed imaging test of the lungs that can be used to better look at these lung patches and also detect inflammation of the airways, inflammatory nodules or granuloma (small non-cancerous clusters of immune cells) and fluid in the lung.

Lung function tests

- These are specialist breathing tests that measure how much air you breathe in and out (known as spirometry) and how quickly you can blow out (peak flow). In addition to a fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) test, a test that measures the amount of inflammation in your breath, these can be used to diagnose asthma.

Bronchoscopy

- During a bronchoscopy test, a thin, flexible tube is passed through your mouth, down your throat and into your lungs. The tube has a camera at the end so your lungs can be inspected. Fluid can be passed down the tube to “wash out” the lungs and this fluid can be retrieved and sent to the lab for analysis. In active EGPA this fluid can show high numbers of eosinophils and may also contain red blood cells. Biopsies can also be taken during this test. This test is particularly useful in making sure other problems which may mimic EGPA, like infections and cancers, are ruled out.

Sinus imaging

- CT or MRI scans of the sinuses can be useful in detecting sinus inflammation and polyps that can occur in individuals with EGPA. A flexible nasendoscopy (FNE) test can also be performed by an ENT specialist which involves passing a thin, flexible tube called a nasendoscope with a small camera on the end into your nostril and gently backwards to look at your sinuses. This device can also be used for local treatment.

Heart tests

- The biggest cause of death for people living with EGPA is heart disease so it is important to perform a number of heart tests to assess this organ thoroughly. These include:

- Blood tests called troponin and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) that can indicate heart stretching, inflammation or damage.

- A heart tracing or electrocardiogram (ECG) to look at the rate, rhythm and electrical activity of the heart.

- Ultrasound of the heart (echocardiogram) which uses sound waves to create pictures of the blood flow through the chambers and valves of the heart and measure its function.

- Cardiac MRI scan which uses radio waves and a magnetic field to make highly detailed images of the structure and function of the heart.

Biopsy

- Obtaining a tissue sample (biopsy) is often the most conclusive test to confirm a diagnosis of EGPA. Biopsies may be taken from any affected tissue (e.g. skin, lungs, nerves, kidney etc.) and may show high numbers of eosinophils, special proteins produced by eosinophils, granulomas and/or vasculitis.

What are the treatment options for EGPA?

If you are diagnosed with EGPA, what treatment you are given will depend on how severe your disease is:

- Severe disease is the term used when there is a risk of organ failure (i.e. when the heart or kidney is involved, for example) or death.

- Non-severe disease is when the symptoms you experience are not organ- or life-threatening.

Your doctor should use the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (BVAS) and Five-Factor Score (FFS) to score your symptoms of EGPA with higher scores meaning a worse potential outcome. These are also helpful to guide treatment choices.

The aims of treatment are to:

- Induce ‘remission’: i.e. cause the signs and symptoms of active EGPA to decrease and disappear.

- Maintain ‘remission’: i.e. Help keep the disease in remission after remission has been achieved.

- Prevent ‘relapse’: Prevent symptoms and signs of active disease returning after a period of ‘remission’.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids or ‘steroids’ like prednisolone are central to the treatment of many forms of vasculitis including EGPA. They provide a strong anti-inflammatory effect and are effective in reducing eosinophils. If you have severe disease, steroids are often needed at higher doses initially and can either be given as an intravenous (IV) drip or tablets. The former option is often used in the most severe circumstances though there is little evidence this provides any additional benefit when compared with high-dose tablets. Steroids are also used in non-severe disease, but often at lower doses. Inhaled steroids are prescribed in addition to tablet steroids for those diagnosed with asthma to reduce airway inflammation and improve asthma symptom control. Steroids can also be prescribed in the form of nasal sprays and drops to control nose and sinus disease. These can help ease symptoms of congestion and try to restore or preserve sense of smell.

Despite their positive effects, steroids carry many long-term side-effects (see section on corticosteroids for more information) so they should be carefully tapered down and ideally off. This can take weeks to months to years depending on the individual.

If you have active severe EGPA, additional treatment options based on international recommendations include:

Cyclophosphamide

Steroids are often not enough on their own to cause remission in someone with severe active EGPA so other treatments are used in combination. Cyclophosphamide is one of these treatments. It can also be given IV or as oral tablets though the former is preferred in most cases to reduce side-effects. To limit these side-effects further cyclophosphamide is usually only given for a few weeks to months. Please refer to the cyclophosphamide section for more information.

Rituximab

Rituximab is an antibody medicine frequently used for the treatment of AAV. It targets B cells, a type of white blood cell in the immune system that produces antibodies. Rituximab is given as an IV drip and can help reducing steroid doses over time.

If you have active non-severe EGPA, treatment options include:

Anti-IL-5/5R biologics

Biological drugs that target a specific protein (IL-5) and receptor (IL-5 receptor alpha) in the immune system that is involved with eosinophil production and inflammation have revolutionised management of severe eosinophilic asthma in recent years. 2 of these medications, mepolizumab and benralizumab, are given as subcutaneous (under-the-skin) injections and are extremely effective in reducing the number of eosinophils in the bloodstream and their effects. They have been shown to successfully control disease in EGPA clinical trials whilst reducing numbers of relapses and help reduction of steroids. This has led to their licensing in EGPA in the EU and the USA. The EGPA licensing for benralizumab is currently being assessed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK, but mepolizumab or benralizumab can currently be prescribed in the UK if you have severe eosinophilic asthma as part of your EGPA.

Azathioprine (AZA)

Azathioprine is atype of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD). It’s used to reduce the activity of the immune system for people with certain diseases. Azathioprine can be prescribed in non-severe EGPA in cases that don’t meet the criteria for anti-IL-5/5R biologics. It can be taken as daily tablet(s) and may be useful in certain individuals who are struggling to reduce their steroid doses without their EGPA becoming more active. A specific blood test is needed before starting azathioprine as some people lack the enzyme needed to break it down leading to side effects.

Methotrexate (MTX)

Methotrexate is another type of DMARD. It can be prescribed in non-severe EGPA in cases that don’t meet the criteria for anti-IL-5/5R biologics. Methotrexate can be taken as a tablet or injection and should be taken on the same day once a week. It is also used by doctors to treat other conditions, such as cancer, but the dose used for cancer is much higher than for EGPA.

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF)

Mycophenolate mofetil or MMF is another type of DMARD that can be taken as a tablet once or twice a day. Like all DMARDs, MMF reduces how active your disease is by reducing the activity of the immune system, rather than just treating the symptoms. Similar to other DMARDs, MMF doesn’t work immediately and can take a few months to take full effect, so it is prescribed alongside steroids or other treatments.

If your EGPA has entered remission after initial ‘induction’ treatment, the current ‘remission maintenance’ options include:

Anti-IL-5/5R biologics (if available) and/or rituximab.

These therapies are most effective at controlling disease whilst allowing reduction of corticosteroids once remission has been achieved. Azathioprine, methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil can also be used whilst lowering steroids. Steroids should be tapered to the lowest possible effective dose whilst maintaining disease remission. How long this takes depends on your clinical condition, consideration of side effects, preferences and values.

There is ongoing research to identify new safe and effective treatments for people living with EGPA. There is no evidence that alternative medicines are useful in EGPA, and they should not be used in place of the above medical treatments.

Is there any way to prevent EGPA?

Unfortunately, we do not yet know any ways to prevent EGPA, but by raising awareness we can hopefully recognise and treat it earlier and prevent lasting damage.

What is the prognosis for EGPA?

There is no cure for EGPA yet, but it is treatable. In the past, you were more likely to die than not if you were diagnosed with EGPA, with people with involvement of the heart, kidneys, digestive tract and brain at higher risk, but with earlier recognition and modern advances in treatments much improved survival and quality of life is seen. Currently, more than 8 in every 10 people diagnosed with EGPA are still alive 5 years after diagnosis and most people with EGPA can achieve remission (i.e. no active symptoms) with the use of the medications listed in the treatment section with no significant effect on life expectancy. Treatment is often required throughout your lifetime as stopping treatment frequently leads to symptoms coming back (relapses). Your healthcare provider will continue to monitor your disease and treatment-related side effects throughout your lifetime.

Living with EGPA

Living with EGPA can be difficult at times but your healthcare provider will aim to support you and provide you with tools to better support yourself. The treatments available for EGPA affect the immune system which may lead to more infections. If you do get infections or you’re taking antibiotics, it’s important you know what to do with your steroids, as there are specific rules for this scenario. It’s important you notify your healthcare provider of any new symptoms or potential treatment side effects so these can be managed. Finally, a healthy diet and lifestyle is encouraged, particularly focusing on prioritising regular exercise and good heart health.

Vasculitis UK Summary & Conclusion

EGPA is a rare form of vasculitis and can be difficult to diagnose. Different symptoms and signs can occur at different times which can lead to a delay in diagnosis. This often requires input from different specialties as part of a multi-disciplinary team. There is no cure for EGPA, but advances in treatment have significantly improved survival and quality of life. Organisations and charities like Vasculitis UK can help you find other people with EGPA for further lived experience and support.

Related Vasculitis Articles

The Immune System and Autoimmune Disease

Further Reading

The 2025 British Society for Rheumatology management recommendations for ANCA-associated vasculitis – Biddle K, et al. Rheumatology. 2025.

EULAR recommendations for the management of ANCA-associated vasculitis: 2022 update – Hellmich B, et al. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2024.

Evidence-Based Guideline for the diagnosis and management of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis – Emmi G, et al. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2023.

2021 American College of Rheumatology/Vasculitis Foundation Guideline for the Management of ANCA-associated vasculitis – Chung SA, et al. Arthritis Care & Research. 2021.

Useful links

Our Useful Vasculitis Links page contains contact details for organisations offering help and support for people with EGPA and other types of vasculitis.

Personal story

You can read one person’s experience of living with EGPA here: Emma’s story.

[This page is available to download as a PDF]